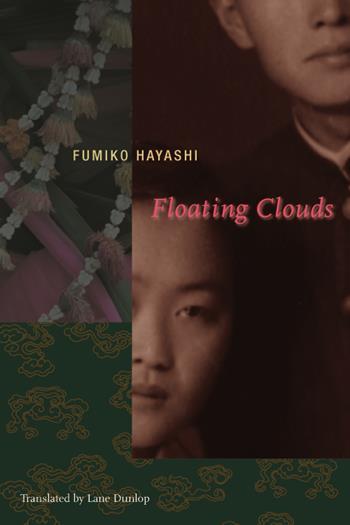

Hayashi Fumiko wrote the novel Floating Clouds, which is a long novel and also the last novel of her. She was a novelist and poet who had a hard life, but she never gives up on writing. it is attractive and impressive.

The main character of Floating Clouds is a woman whose name is Koda Yukiko. She went to work at French Indochina during the war, and met a man named Tomioka, who she fell in love with. However, it was an affair between and it was an unethical thing even though Yukiko really loved him. After the war, Tomioka returned to his wife, but he did not cut off his connection with Yukiko. It seems that Yukiko always knows Tomioka has wife but she still can not stopping love him. Tomioka never stopped torturing her, and he even fell in love with someone else while Yukiko was pregnant, so she had to do abortion. I hate the man so much while I was reading this part because that was not only the mental destruction but also the damage of Yukiko’s health.

What never change is Yukiko loves Tomioka and she does not hide her feeling at all. Readers might think she is a fool and they do not understand her thoughts and behavior, but I think that’s what woman will do when they love someone so much. Yukiko might be a little crazy, but she is understandable. She always follows her heart and does not care about other factors, which makes me admire her courage.

Nevertheless, Tomioka is very different from Yukiko. His love is not as purely as Yukiko’s, and his love depends on the social environment. Tomioka is selfish and he is always affected by other factors, which means he has inconstant love. He also “controls” Yukiko by using her obsession.

The writer Hayashi Fumiko expresses her thoughts and opinions of the difference between men and women. Women are passive in the relationship because they pay out too much on love, so that women’s love are persistent and selfless. According to Fumiko, men’s affections are unstable and selfish.